By John Malkin

Listen to the interview below:

Part 1

Part 2

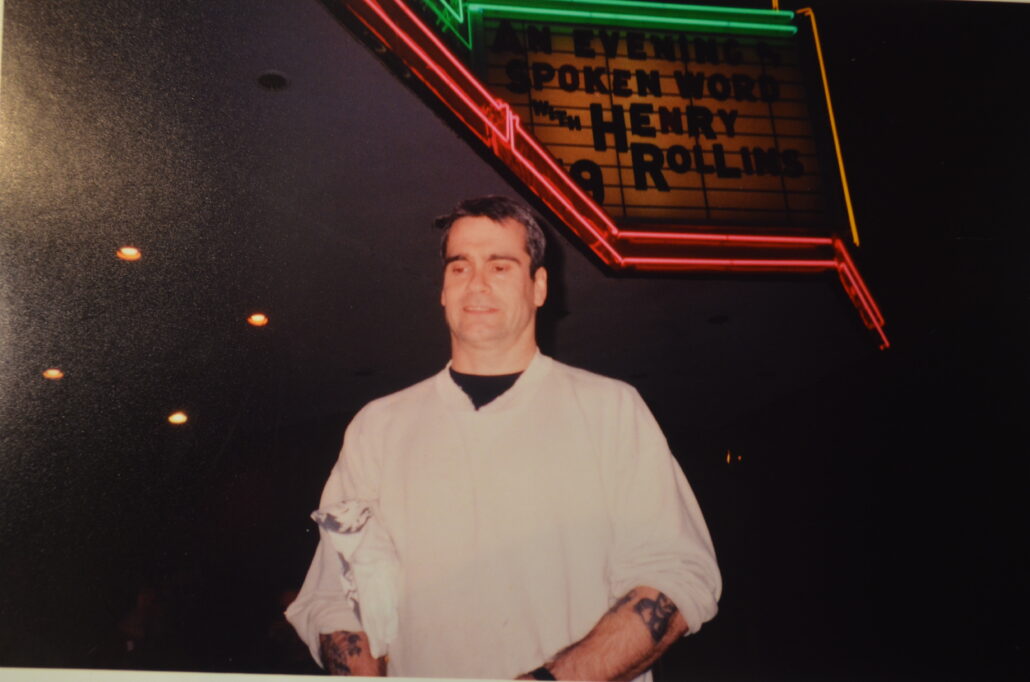

After a successful 30-year career as a punk rock singer with Black Flag and Rollins Band, as well as being a publisher and actor, Henry Rollins has evolved into what he describes as a “low-grade journalist.” Rollins writes for the LA Weekly, hosts a weekly program on KCRW and for three decades has journeyed the globe with a still camera to experience and document the world; from beautiful vistas in Peru, to warzones of Iraq and Afghanistan and impoverished shanty-towns of Bangladesh, India and Sudan. The man who once sang “Gimme Gimme Gimme” and “Low Self Opinion” is now sharing images and insights from his travels to Asia, Africa, South America, Antarctica and the Middle East and his overall assessment is not good; the planet is suffering from huge social-economic inequalities and potentially devastating changes to the climate. Henry Rollins’ 2018 Traveling Slideshow was at the Rio Theatre in Santa Cruz on October 27, 2018. The interview was recorded on September 14, 2018.

The following interview was originally broadcast on “Transformation Highway” with John Malkin on KZSC 88.1 FM and portions were published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel on October 24, 2018

DO YOU JUGGLE?

JM: “Is this the first time you’re touring with your photos?”

Henry Rollins: “To be hyper-technical, a few years ago I showed photos at the National Geographic Theater in Washington DC. And then I did another free show at the Annenberg Institute in Los Angeles. As far as a ticketed event like, “Don’t screw this up,” I had two nights off in Australia on the 2016 tour. I don’t like nights off. So, I said to my agent, “What’s with these nights off?” And as a joke he said, “Well, do you do anything else? Do you juggle?” I said, “I’ve got this slide show.” And he said, “Okay, we’ll book that.” All of a sudden it turned into a real thing and we did the Sydney Opera House and Brisbane. As a real event, that you paid your hard-earned money for, it actually came off really well.

Then my road manager and I said, “Well, let’s talk to management and see if we can do more shows.” The agent seemed to like the idea and we bought a computer dedicated to the slide show, so all the RAM could be devoted to one purpose. And my very smart road manager learned all kinds of new techs for a new tech rider we have to be hurling at venues for hi-resolution projectors and what not. This tour, where I’m coming to see you guys, is basically the second half. Because January and February we were out on the road doing this in America and Europe and then I had a whole bunch of other work to do, which just finished four days ago. So, I’ll be able to resume the tour and do Midwest to the West coast and then hop back to Europe and end in either Kiev or Iceland. We’re waiting on a show in Reykjavik. It’ll come through or it won’t. But the show in Kiev; tickets are on sale.”

FIRST TIME OUTING

JM: “In your previous spoken word tours you’ve often told stories about your travels to Iraq, Afghanistan and other spots. Do some of the photos in this tour come from your 2011 book Occupants?”

Henry Rollins: “A few of them. I’m trying to concentrate on newer stuff that I’m more excited about. But yes, there’s definitely a fair handful of photos from the book Occupants. Because the stories are good, it’s a good thing to have that image on the screen and me going, “Here’s where I was. Here’s what it was like.” My gut instinct is always to go with newer material. Keep things moving briskly so you never have a chance to rest on your laurels. But this being a first-time outing with the slides, I’m definitely taking everything I’ve done and picking out that which makes for a good tell, when I’m showing an image. If I ever do a tour like this again, immediately all the photos that you would see on this tour would have to go. You can’t show them twice. So, it might take me awhile to assemble sixty-five or seventy-five images that are worthwhile to make an audience sit and endure me talking about them.”

HAITI: RUBBLE IN PLACES

JM: “What are more recent travels that have been the most inspiring or have affected you the most?”

Henry Rollins: “A trip to Haiti was really upsetting. (2011) It had been years since the earthquake and the place looks like a monster stomped on it or an airstrike happened. It’s just rubble in places. I just don’t understand – this is a country on planet earth. Why is it like this? I know NGO’s have been there. I was with some NGO’s there, working with orphans. I’ve seen great people doing stuff but it’s still a real sad place. It’s amazing how Homosapiens can just let other Homosapiens just kind of slide. At some point we’re okay with this. I’m not!

I went there on my own with a bunch of money and I found a local guy and hired him to drive me around. Since he was local, he hopefully got me a good exchange rate. Everyday we’d take American cash and translate it into Haitian money and go buy stuff like soccer balls and water and make cash donations to orphanages. Just one guy trying to help – it probably didn’t do much. Maybe better than nothing. And ninety minutes or less and you’re in Miami. “Wait a minute! This is just down the road.” It was a helluva’ trip.”

ANTARCTICA: GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE IS REAL

Henry Rollins: “I had a recent trip to Antarctica where you see everything from the beauty of it – which is staggering – all the way to the tragic. My experience was I felt I was walking around in a dream. Or maybe it’s what it’s like to be on the moon because it’s just so foreign to anywhere I’ve ever been before. “Hey, there’s a penguin walking by! And there’s a seal on the beach!” It was surreal and the beauty is kind of overwhelming.

And then you go to the edge of the Antarctic Peninsula and you see old car transmissions and an airplane hangar at places that were set up to render whales and seals almost to the point of extinction. The money came in and the deregulation and these animals were killed off. You realize, “There’s nowhere on the planet – the only planet I’ve got – where my species hasn’t done damage.” And you have to get so far away from them it’s not even funny. (laughter) I share being Homosapiens with these people but I don’t even want to name them. How could members of my species do this? They left their trash on the island! There’s a frickin’ car transmission sunk into the sand with waves lapping over it! You can’t even get away from us all the way at the bottom of the world.

I traveled on this ship full of scientists, so everyday I’m going to lectures and they’re showing you, “Here’s an iceberg.” Jump cut over a few years and the thing is shrinking in front of you. Global climate change is real. When you see it like that, when you see cold weather penguins like the Adélie, now further south than they’ve ever been. Or the Gentoo penguins breeding where the Adélie used to because they had to move to cooler territory because their territory to breed is now too warm. They’re going to places they’ve never been before. Even the animals are telling us that global climate change is real. That was really upsetting.

I was with hardcore scientists and I said, “What does this mean?” And they’d say, “Oh, we’re screwed! We’re done.” I said, “Well, what about making things better?” They’d say, “Yeah, that’s nice. We can slow the train down a little, but this thing’s hitting the side of the mountain.” From the industrial revolution on, this has been our lot. It was grim. That’s the kind of travel I’m compelled to do yet I can’t come back with anything that’s all that cheerful. You could make a cute penguin story, but that’s an animal at risk because of us.”

AMAZON: CO-EXIST WITH NATURE

JM: “We live on a planet that is paradise with fruit and vegetables growing out of the earth, like candy, that is beautiful and nourishes us and yet we’re destroying it.”

Henry Rollins: “It’s because we like to take too much of it. And the final nail in the coffin is when you monetize it. While I was in Ecuador a few years ago I got on a tributary of the Amazon called the Napo, on a nature boat with scientists and botanists. You’re out every day getting told how this amazing eco-system works. It’s so fascinating. The only thing that screws it up is man. It’s the oil and the timber, where they’re meeting all these un-contacted people. Well, they’re getting contacted now because a helicopter lands to survey for the timber. And that’s how these people are being contacted for the first time, because the money is defoliating their forest. So, chunks of Ecuador are being sold off for nothing.

It’s causing great disturbances to these amazing cultures of people who really learned to live with nature in pitch-perfect harmony. Where they don’t intrude, they co-exist with nature. And in comes the money and that’s the death nail. I’m not against Capitalism, but man it can go south on you. It’s like trying to carry nine glasses of nitroglycerin through a busy nightclub and hope that’s going to go okay.”

THE WEST HOLDS THE WHIP

Henry Rollins: “The thing I’ve seen in all these places is: humans. And when things get monetized, there’s destruction. As soon as you monetize it, you weaponize it. And there’s always someone on the bad end of that deal. From all the travel I’ve done, what I’ve come back with is this; the West holds the handle of the whip and it’s other parts of the world that feel the lash. The sweatshop isn’t here; the cheap clothing at Walmart is here. Where you just put on the clothes and go about you’re business. You like the savings. But there is someone making those clothes who is living in a dorm with three other people who don’t see home except twice a year and they’re sending the money home. They get an appalling wage that if you put it on Americans, they’d riot. Yet, you have people saying, “Minimum wage? Fifteen dollars? No!” – “Really? That’s too much, huh? You don’t want to let people live decently?” That’s nothing compared to how people live in other parts of the world.

I need to know this stuff so I have something on stage to talk about. And it’s not always fun. So, I temper the shows with stuff that’s a bit lighter. There’s some laughs to be had. But in order to get through this century, you have to know this stuff. Or at least know enough, or have seen enough, to feel some responsibility. So somehow, as cool as you are, you are somehow part of it for better or for worse. So, you can choose to be part of the better part of it and that’s a tricky deal. It takes more than giving a hundred bucks to the Red Cross. It’s quite involved. It’s much easier to go, “Oh, yeah, hearts and prayers.” (laughter) I just can’t do that ‘cause I know what a non-solution that is. So, at this point I’m just compelled to go to these places. Not in a voyeuristic-got-the-intense-photo-and-run-home kind of way. I’m trying to get an understanding and that’s why I go and go and go. And return and return and return.”

PREDATORY CAPITALISM

JM: “Would you say more about Capitalism? It resonates with me that monetization and weaponization are ruining cultures and making everything for sale; water, air, the earth, ideas. How is monetization different than Capitalism? Our culture tends not to be very critical of Capitalism and we’re all taught that Capitalism was a wonderful thing that developed intuitively when humans said, “Hey, I want to trade two goats for six bales of hay,” and that became too cumbersome. But I think it’s Capitalism you’re talking about when you say that nature and cultures have been monetized and weaponized.”

Henry Rollins: “It’s what Capitalism does. There’s professors that devote their life to this discussion. I’m a high school graduate – I don’t know much, not compared to some PhD. My street view of Capitalism is this; it’s clay. You can make it into anything. You can make it into a thing for good or you can also weaponize it. There’s predatory Capitalism. The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein – that’s one of the best books I’ve ever read, about how you can destroy cultures with Capitalism. You can also take them out of ruin with Capitalism. It’s more about the person wielding Capitalism than this thing itself, because you can make it do your bidding. There’s some people, like the real rich, like the Gates family. Bill Gates and his wife cut loose gajillions of dollars for good – cool! They’re making things better with that massive amount of money they make per hour. As far as I can tell, they’re not part of a problem. But then there’s companies like Monsanto who I think are Darth Vader in a building. That to me is the weaponizing of money.”

SOUTH SUDAN: WATER PROBLEM

Henry Rollins: “You mentioned water. Water and the lack of it and the control of it weaponizes your own existence against you. If you don’t have water, you’re dead. There’s a lot of people in the world; they have no idea that the water under their feet is being re-directed. It got bought! Nestle’ bought it and they’re redirecting and extracting it. And water that you’re going to need for your cows and your crops or for your kid? That’s going somewhere else. Like the Mundari, the group of nomadic cattlemen that I saw in South Sudan some years ago; they’re going to have problems because cows take up a lot of water and South Sudan has a water problem. And that can be used against them. People are really easy to break because we’re a needy species. There’s nothing you’re going to be able to tough out if I take your water away for three days – you’re done. I don’t care how macho anyone thinks they are; three days without water and I ‘gotcha.

This is where the West holds the handle of the lash and the rest of the world cowers. This is nothing new. The Brits were good at it and the Belgians and the French. The Americans and even sometime the Canadians. It’s what people do to each other. It’s where good ideas go and become monstrous ideas. It goes from the trading idea; “I’ll trade you two sacks of flour for enough timber to get my fireplace through the winter.” That’s nice. But then someone opens a store. I’m not putting any of this down because Capitalism allows me to eat because I work and I get paid and when I go to the supermarket the guy wants money – not hugs – for me to get my groceries. So, I rely on Capitalism yet I see how corruptive and corrosive it can be. It’s a weapon and if you use it really carefully you might not hurt too many people. But by and large, someone is going to get hurt.”

GET OUT OF PODUNK

JM: “I want to ask you about militarism from a punk rock point of view, or points of views. As you mentioned, the United States is benefiting off the rest of the world. I’d like to throw you four short punk rock scenarios and see what you think; Justin Sane and the band Anti-Flag have tried to stop military recruiting in schools. The Vandals had backlash from fans and show producers after the band performed for U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. You’ve also performed for U.S. troops in the Middle East. A total other side of this; the U.S. military used to blast Rage Against the Machine songs, and other music, as part of a system of torturing people at Guantanamo Bay. Tom Morello and Billy Bragg complained about this and I think made them stop. And the band Gang of Four explored selling, “I Love A Man in a Uniform” for a U.S. military recruiting TV commercial. The military approached them and eventually backed out of the idea. What’s the relationship between music, creativity and punk rock with this whip and lash of America?”

Henry Rollins: “Well, as far as my performances with the USO for the enlisted men or women – they don’t set policy. They take their orders. So, my disagreements with the invasion and occupation of Iraq; it wasn’t with infantry. It was with Dick Cheney and all his golfing buddies. So, when I’m in Afghanistan or Iraq with a bunch of soldiers, getting mad at them is like getting mad at the person behind the counter at the airport because the flight is late. “I understand your anger, but I didn’t make the flight late. This is just a job.” For a lot of Americans, being in the military is a way to get out of Podunk. It’s a way to get out of the town you live where consistently all the males in your family have drunk themselves to death and lost an arm in the combine or something, and they bail. And they go in the military. Or the 9/11 crisis inspired them to go get in there – whatever compelled them. My arguments are not with members of the military, at least on the infantry level. My argument is with the ones who send them. It’s the people like Condoleezza Rice who just lie. That’s why I do USO shows. I wanted to meet these people and see these places and get an aspect on this whole thing that there’s no way I’m going to get by listening to Wolf Blitzer tell me about it. I did a lot of USO work and met some amazing people and had some fairly healthy arguments with some of the higher-ups, where we disagreed a lot.”

SOLD OUT / MUSIC WITHOUT RESTRAINT

Henry Rollins: “I don’t exactly know what punk rock is supposed to do in all of this, or what it’s supposed to mean. To me punk rock is a very personal and individual thing, like a thumbprint. There’s this weird imaginary rulebook. Like people say, “You did that? You sold out!” – “Really? Where did that come from? Is that in the Constitution? You’re my moral guy now? Let’s take it to court. Let’s take it anywhere where you’ve got to prove that!” When you put it to someone that way, it just never holds up. That’s where I’m at – I just do stuff and if someone doesn’t like it – “Okay, I sold out. According to you. I think you sold out because you’re thirty-eight and you still live with your mom! So there!” I don’t know what responsibility musicians or artists have necessarily to society besides doing their music or their painting without restraint.”

DIDN’T CUT MY HAIR AGAIN UNTIL 1986

JM: “I view punk rock at least partly as having to do with living free or experimenting with creativity and expression. Punk went down a lot of different paths very quickly and some of those paths became uniform and started saying, “If you don’t look or sound a certain way than you’re not punk.” That’s not limited to the punk rock world. There’s some human tendency to categorize, contain and label. Maybe like Capitalism, it’s a structure that can seem helpful. But it then becomes limiting and a form of violence. I’m thinking of when you were in Black Flag. I think it riled people up when you grew your hair long or when the musicality of Black Flag slowed down and incorporated more of a metal sound. I’d like to hear more about your experiences with being told to be a certain way.”

Henry Rollins: “Yeah, sure. In 1982 we were in New Orleans one night and someone gave us all these Mardi Gras beads, like a bag of ‘em. And (Chuck) Dukowski, the bass player, put four or five of these crazy plastic necklaces around his neck. (laughter) Wherever we went the next night – Tallahassee or Atlanta – he was taking the beads off his neck and putting them around necks of the people in the front row at the Black Flag show and saying, “Here, my flower child.” People were getting so mad! You know, long stream of expletives! I think I had my hair about half an inch long and someone told me to get a haircut that night! And I didn’t cut my hair again until 1986. In fact, there’s photos of me on that tour with a beard. I just stopped shaving. I didn’t shave again until July 6th or 7th, when the tour ended. I hated having a beard – it was just awful! (laughter) But I just went, “Well, we’ll just try this out.” I looked like some weird guy by the end of that tour. There’s lots of photos of it and the hair grew quite quickly in my youth. I just let it grow. “Okay, I’m a hippie now. Whatever you want.”

As far as the music slowing down, man, ask Greg Ginn. Black Flag was his band – he wrote all that stuff. It’s what he was feeling. It was his band and we were in it. That’s why he had the turnover rate. Some people didn’t want to ride on the train anymore. They stepped off and no one else stepped on. Me; I had nowhere else to go. I just stayed with it. It was Ginn’s machine and he’d hand you the lyrics. I wrote song lyrics here and there when he didn’t have lyrics for a song. He’d say, “Hey, you can have this one if you want,” and I’d put some lyrics to it. But as far as the direction musically for Black Flag – that was about 99.999 percent Greg. And when someone didn’t like the song, they would usually take their anger out on the singer. So that’s why I got all the bottles, ashtrays and the cigarettes into my legs and the bic lighters underneath certain parts of my body. ‘Cause you ‘gotta keep those warm. So, I’m the one who got the concussions and all the stitches for those songs.”

JM: “I’ve spoken with a lot of punk rock folks about how punk changed at some point and slam dancing turned into gang fights and this thing of throwing stuff at the performers. Oddly enough, what you just said about bic lighters reminds me of an interview I did with band members from a band called Blackfire, maybe the only Native American punk band. Clayson Benally told me how difficult it was to be an indigenous youth in America and he said, “I was not treated well and one day some kids at school cornered me and held me down and branded me.” I said, “You don’t mean actually branded?” And he said, “Yeah, they held me down and took a bic lighter and heated it up for a while and branded me.” He still has the scar. How did you cope with stuff getting thrown at you and people punching you and all of that?”

Henry Rollins: “I became it. I became my surroundings. I’m almost sixty and to this day I hear things like, “My friend met you in 1983 and he moved and you shoved him.” I’m like, “Yeah. He moved. I probably wanted to get him away from me.” As some guys will say, “It was the training.” And that was my environment. If I had a dollar for every time some girl would come to our van in the parking lot of some crap venue we were going to toil in that night and said, “My boyfriend is a skinhead and he’s going to come here and beat you up tonight.” – “Thanks. I’ll put that under the pillow and smoke it in the morning.”

And more often than not, I’d be loading out the gear after playing a show for a six dollar and fifty-cent ticket, because I don’t have a road crew, I’d be loading our gear out to our miserable vehicle and there’d be the guy waiting. Just like the 3:00 PM guy after school. You know, “Hold on. Let me go get the kick drum and then we’ll fight. I’ll be right back.” It just became a utilitarian part of my life. Just aim for the nose, get it over quickly and then, “I ‘gotta get the drum stands now. I hate that box; it’s so heavy.” I’d go right back to work! (laughter) Or it would happen during the show. Like, “Okay, next song. Boop! Neutralized that guy. Here comes the chorus.” It just became part of the thing. And I just got used to it.

I’m not good at fighting. I’m not a tough guy. I’m not tough at all. But I just became the environment. And then sadly, when the nice guy comes up, “Hey, man!” I’m like, “Argghh!” He’s like, “You’re a jerk.” – “Well, okay. I am, the last four hundred and eighty shows.” I’m not excusing bad behavior. I’m just telling you that’s part of the reason those things happened; that was the environment.”

SKINHEADS BEHIND THE COPS

Henry Rollins: “You look out into the audience and go, “Whoah! That’s a stabbing. Okay, we got two more songs before the cops come.” And the kid would be bleeding. Thankfully not life-threatening. And the cops would come and the sheriff would take the mic, “The show is over.” They’d never give you back the mic. They’d just drop it on the stage. First time I ever saw anyone drop the mic! And that would be the end of the show, and you’d have to load the gear out.

One time in Florida, these skinheads beat up our soundman. And beat him up like a “Rocky III” makeup job, with both eyes closed. They basically found him and tackled him. They pulled the chords out of the PA’s and the stage right stack went out. So, the soundman went to go see what was wrong and they were waiting for him and they stomped on him. And the cops came and all the skinheads got behind the cops and the cops told us to pack our gear and get out of the county. Because they’re all friends with the cops, these skinheads. They were all standing behind the cops, sieg-heiling and flipping us off. That was a typical night for Black Flag.

So, after a lot of those experiences in America and England and Holland and Scotland and Germany. And Canada. After a while you’re like, “Okay!” That’s how it is.” You become that, you become your surroundings. I guess it’s like what happens to someone in jail. That’s kind of what happened to me. And it took a long time to kind of launder that out of myself. To get that out of my system.”

LINING UP THE SHOT

JM: “Are you willing to say a little more about how you laundered that out of your system? A lot of us are trying to launder different things out of our systems. I’m fifty-five and I have to say that over the years I’ve viewed you – Henry Rollins – as being that intense guy who’s getting into fights. In the meantime, I’ve gone to your spoken word performances and thought, “Wow, Henry is really thoughtful and coherent in explaining his ideas and experiences. And pretty damn funny, too.” One thing I was surprised about when I first heard you talk about it was your love for King Crimson. I thought, “Really?” And you spoke about a project you worked on with William Shatner and Adrian Belew. We’re all multi-dimensional. Would you say more about how you laundered out some of the anger?”

Henry Rollins: “Sure. Chuck D, who is amazing, said in an interview once, when a guy asked, “Why are you so Black?” Chuck said, “We’ll stop being so Black when you all stop being so White!” I thought, “Wow. That’s intense.” But I get it. I’ll put my guard down when people stopped putting their dukes up. “Oh, cool!” It’s not smart to put your guard down, cause that’s when you get knocked out. “But this guy doesn’t have his fists up. And then another one doesn’t have his fists up.” Okay, then I have to land my ship and see how to navigate this new land. A land that’s not nearly as hostile and combative as it was two summers before. That’s where someone taps you on the shoulder and you turn around and have to take your hand off of their trachea. Because that’s all you know. It’s probably a strain of PTSD.

But after a while it’s like, “Okay. Maybe there are other ways to be around people at shows, because not all of them are coming to unload on you.” It took a while to get off of that. Because I’m not really into being hit in the face. It’s not really what I’m into. So, it took me a while to go, “Oh, not everyone’s trying to do that.” I certainly knew that but it took me awhile to just consider, “Okay, how do I comport myself around males where I’m not looking for the line.” I still do it to this day sometimes. I’ll be standing with another male and I’ll find myself thinking, “Okay, I move my left foot three inches, dip my shoulder, and the quickest line to this guy is going to be… his right jaw.” I’m still lining up the shot. It’s just from so many years of that being probably a pretty good way to assess a male talking to me.

You know, the crowds at shows changed dramatically. 1986 was the peak of all of that combative behavior. But by ‘88 it just seemed to be over, or at least at my shows. Maybe those kinds of people heard the music I was making and went, “This sucks. We’ll go elsewhere.” – “Fine.” But we just kind of stopped having that happen at shows, almost completely. After a few years of that, you go, “Well then, let’s use more colors on the palette with how we relate.” That was a growing experience.”

PUBLIC PROPERTY

Henry Rollins: “And from there on I had this awkward few years getting used to ever increasing recognizability. You could call it fame but that’s a little weird to me. I started getting recognized more and more from being in a film, being on TV, stuff like that. Being on Jay Leno or whatever. Where people would stop me and you’re almost like public property, where someone just puts their hands on you. They grab you, “Henry!” – “Whoah! What?” (laughter) Like, “Where’d my coffee go?” – “It’s on the ceiling!” It just rattles your nerves and it took me quite a while to get used to people just walking up and talking to me at the airport, in a hotel lobby, in the elevator. The pilot of the plane wants to meet me? So, that was another bit of growing that I had to do. And now that kind of thing gets more and more intense especially with social media and cell phones.”

LIFE IS REALLY SHORT

Henry Rollins: “That’s how I parts-per-millioned this thing out of me. It was basically a de-escalation; “We’re moving the missiles out of Cuba.” – “That allows me to take my missiles out of Turkey.” You know what I mean? Kind of an obscure historical reference. But I don’t want to dislike people. I want to like them and understand them better. It makes me better. And also, life is really short; you’re fifty-five. You see it. It goes by very quickly and to hold onto this stuff gets heavier and more of a burden the longer you carry it. When someone comes up to me and says, “Thirty-five years ago I threw a bottle at your head. I’m really sorry.” I go, “Hey, man, that’s so big of you to say that. It’s cool.” Let’s just get running shoes on and go forward at full speed.”

HIGH FUNCTIONING YET PRIMITIVE

Henry Rollins: “To me people are a wonderful species. We’re high functioning yet primitive at the same time and that becomes a problem. Like, a man with a PhD can be a rapist. Wow. “How do you entertain both of those things?” Well, a human can do it! We’re that incredible. They can be a monster and a professor at the same time. I travel to these places to try and understand the full capacity of humankind. You see the good and the bad, the amazing and the wretched. And you see it all without as much filters. Like in the West, a corpse is shot full of fluids so it doesn’t rot. We have a weird fetish with death. We have this weird thing with death and sex that’s so knotted up. That’s why so many people get busted. You know – “He had an affair with a man!” – “Well, he’s gay.” – “But he’s got three kids!” – “Yeah! He couldn’t be who he was.” We’re so knotted it’s like our intestines are all folded and nothing gets through.

In other parts of the world, you can just walk right up and go, “Wow! That’s a human bone poking out of the ground. Oh. Cambodia.” The history there has got a lot less filters. My first day in India I saw nine or ten dead bodies. I’d ask, “What’s that smoke?” – “Oh, it’s that guy on a pile of wood.” – “Okay.” I walked over and stared at that for twenty minutes. Life and death is right in your face. Where here in the West there’s fences around things or pixelated boxes over the image with a big warning; “This might be upsetting, so get the kids away from the TV set.” I need to see these things to see where humanity hits the wall.”

UNDERSTAND HOW THE WORLD WORKS

Henry Rollins: “In America, in the West, you see humanity at like six point five. You read about it when they hit ten or ten five on the news. In other parts of the world – with things like starvation, the effects of globalization and global climate change and what poverty really looks like – it’s walking by you. It’s right there. I like having all my Western expectations, ideas and mores challenged. It’s good to be, as I like to say, “Busted out.” Where you just go and all of your circuits just get blown out. Like someone cheerfully comes and goes, “No, that actually goes to twenty.” Pow! And five lights go out. I need that. Not because I enjoy the misery of others. I’m just trying to understand how the world works in a very unorthodox way. I’m not all that interested in reading about it. I’m more interested in writing about seeing it directly. And coming back to you with a reportage. That’s what I use the stage for. I’m like the faithful dog that brings the quail back and puts it at your feet.

I’m trying to report back. So, my travel ideas are semi-journalistic in a way. I do a lot of writing while I’m out there and it turns into a magazine article or a book. Or notes for something I’m going to tell on stage. Like with this particular tour, “Here’s a photo of that thing I told you about two years ago, last time I was here on tour.” That’s why I do this stuff.”

DIAMANDA GALAS, PENDERECKI AND BARTOK.

Henry Rollins: “Going back to completely answer your question about King Crimson. Greg Ginn turned me onto King Crimson. I knew the name – I’d never heard the music. He played the live album for me – “Live USA” or whatever it was called. I was like, “Wow. That’ll work.” I became a fan. Listening to National Public Radio, and the station I work at now, KCRW, got me into things like George Crumb and Brian Eno’s solo records. And it was also my mom, who has pitch-perfect taste in music. She turned me onto Bartók and Stravinsky, Chopin, Wagner, Barbara Streisand, Woody and Arlo Guthrie, Dylan and Glen Campbell. She bought from all five corners of the record store. I was raised with music. We didn’t watch much TV but my mom would put on records continuously through the weekends. I took that and by the mid ‘80’s I was into Diamanda Galas, Penderecki

and Béla Bartók. My bandmates were like, “What’s this shit?” – “Well, it’s interesting.” My Black Flag bandmates were completely not hearing this stuff. I was always fascinated by Laurie Anderson and all this music I was getting turned onto. I was the willing student and by this point I was into music that clears rooms and is interesting to me. But that started with me musically, really young. I used to take my mom’s record and ask, “Can I borrow this?” She’d say, “No, you can have it. I’ll just go buy another.” That’s how I’d take my mom’s Strauss records and whatever else.”

MUSIC: A LIMITLESS UNIVERSE

JM: “I also really love Brian Eno, Laurie Anderson, Bartók and John Cage.”

Henry Rollins: “These are amazing people and if you’re in the right mindset you realize that music is this limitless universe and all you’ll ever be is a student. Everyone says, “I know quite a bit about music.” I think, “That’s such a tell! No, you don’t!” Because if you knew anything about music you’d know how little you know about music! (laughter) The best is you’ll get is a teaspoon of knowledge of the ocean of music. But you’ll have a really good time trying to get the other eighty-gajillion gallons.”

NEVER ENJOYED MAKING MUSIC

JM: “Do you have interest in forming a new band or producing some music?”

Henry Rollins: “No. For me it was a real time-and-place thing. For me, being in a band was like having an intense virus. It hurt. It caused me a lot of pain. And it passed through me and one day I didn’t have it anymore. I never enjoyed making music. Never. And that’s how I know it was real. I never liked band practice. I didn’t like being in a band with other people, and wanting to kill the bass player every day. Playing was painful – physically painful and mentally excruciating. But it was in me and it had to come out. So, once it was done, I stopped. I remember I woke up in my bed one day – I was off the road – and I went, “Wow, I’m done. Huh.” I just sat there for about twenty minutes tripping on that. I had this imaginary diploma in my hand and someone was gently pushing me off the campus. I called my manager at the time and said, “Hey, I’m done with music.” And he saw fifteen percent of that going away, which was quite a lot of money for him. He said, “No, no, no! We will…” I said, “We?” You’re not on stage!” But, okay, we’ll go with it. He says, “We could do a greatest hits tour!” I said, “No. I never wrote any of those. And… no!””

IMPLIED RISK

Henry Rollins: “I need to live with a certain amount of implied risk in my life. I would say artistic risk but I’m not an artist. But I don’t want to go out and play the dubious hits because that’s fighting a pre-fought war. You’re just a war re-enactor. You’re going back in pantomime, for me at least. I had this discussion with one of the most famous rock singers in the world, responsible for at least seventy-five or eighty million records sold and one of the nicest people I’ve ever met. I said, “You go out there and sing at least seven to ten of those same songs for the last thirty years.” He said, “Yeah.” I asked, “Why?” He said, “Because I want to make people happy. Don’t you want to make people happy?” I said, “No. Not necessarily. (laughter) But that’s what you think the job is.” He’s a couple generations older than me and he went, “Yeah, of course! It’s a show!” I said, “Okay.” I’m not going to argue with the guy. I totally see where he’s coming from. I just don’t feel that obligation.”

FEAR OF FAILURE

Henry Rollins: “I take my artistic inspirations from people like Ian MacKaye, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, who in many ways are very similar. With Ian MacKaye, a guy leaves their band? He breaks the band up. “We need a new drummer.” – “Nah, we’ll start again!” – “The drummer is going away to college so you’re going to break up Minor Threat?” – “Yeah!” – “What are you going to do?” – “I don’t know yet.” – “Okay.” (laughter) And that’s Ian. He just gets on to the next thing. “But what about…” – “What about what? It’s not a career! Next…” Same thing with Miles Davis. You see him in 1970 and it’s one line up and you see him in ’78 it’s something else. My mom has every Miles Davis record up to In A Silent Way. When I was younger and more conversant in Miles Davis I asked her, “Why does it stop at “In A Silent Way” and she said, “I couldn’t understand him anymore.” She used to go see him and Coltrane. Same thing with Coltrane; he just went where it took him. And people would riot about his later material. People would say, “Outta here!” and throw stuff at the stage. I think the last show Elvin Jones ever did with him was in France. People were throwing everything from food to money. Jones went on the stage and picked up all the money and bailed. “Bye John. I just can’t do it.” Because Coltrane would move on and wouldn’t rest on his laurels. I try in my own way to live in that way. “Hey, you want to try acting?” – “Yeah!” – “Can you do it?” – “Well, we’ll see tomorrow morning at 6:00 AM!” So, I just kind of leap into stuff and do the best I can and that keeps my blood thin and it keeps a certain amount of risk ever present. Fear of failure is a fantastic motivator for me. Confidence, to me, is a killer. Once you think you’ve got it, man, that’s when the thing eats you.”

A CALM AND A STRENGTH

JM: “Occupants has your photos from so many different travels. There’s some of war, landmines, kids in Cambodia, a palace in Saudi Arabia, people you connected with in South Africa. I’d like to hear about the photos you took of monks in Burma and Thailand. In the notes at the back of Occupants you comment, “I’m not a spiritual person, but I always like looking at monks. There’s a floating strength about them that I like very much.”

Henry Rollins: “I notice that when I meet Buddhists and Buddhist monks, there seems to be a calm and a strength that is derived from meditation and thought. They’re just cool people to be around. I know that sounds kind of pedestrian but I spend a lot of time in Buddhist countries and there’s just a way they are. “Okay, you don’t have to get aggravated walking up this hill. We can also laugh all the way up the hill.” Instead of going, “Ugh – this sucks!” We can also just make jokes or we can say nothing. And just breathe the air. There’s different ways of going about things.

I’m not an authority at all on Buddhism but what gets to me about Buddhism is that it’s very non-Western. Here we’re supposed to struggle and strive. Buddhists are not what I would call lazy people, getting up at four in the morning; they’re not taking the easy way out. It’s just a different way of going about life that I seem to be able to absorb from monks and people I meet in Buddhist countries that I find fascinating. I don’t know if I’ve been able to incorporate any of it. I think I’m just really high strung. I look at it and I appreciate it and I don’t know what I could do with it except admire and respect it. I really do enjoy Buddhist monks. I have great conversations with monks and rarely do we not end up laughing. I quite enjoy that. But I’m no expert on Buddhism. I’m not a spiritual person; I believe in mortality.”

RELIGION IN AMERICA

JM: “Seems that’s where we’re all headed. I don’t know anyone who’s said, “I got out of it!”

Henry Rollins: “I’m not saying religious people are in denial. But the idea of death for some people is really frickin’ grim. I get it. They believe, “There’s an afterlife, it’s not over.” – “Oh! Whew! Okay, good! Then… we’ll have some more pizza!” – “Well, have the pizza anyway!” (laughter) I’m not interested in crushing someone’s beliefs. When someone says, “You’re an atheist.” – “Nah.” That’s just too much work for me. That’s going over there and saying, “There is no God.” I’m not going to hold that sign.

The only time I have a problem with Western religion in America is when I had to drive by the guy with the “God Hates Fags” sign. Those Topeka folks actually came to Los Angeles a few years ago. They started in the Wilshire district of all places, perhaps because there’s a lot of Jewish folks there, and then they moved right to West Hollywood with their sign. They’re homophobes. They say that the bible instructed them to do this and I’m like, “No. Let’s not take a book and grind it up. That’s just you, man. You should deal with that.” That’s the only time I have a problem with religion, when it crosses the line and breaks the rules of the first, fourteenth and fourth amendments. Other than that, I let people have their beliefs.

I totally understand the idea that there’s something coming later, so you better conduct yourself in a good way now ‘cause you will be made to pay. I think that’s an interesting, somewhat brutal, way of instructing morality, which is a tricky thing anyway. Fear – that can work. But when they get into, “If you masturbate, you’re going to hell.” – “Really? Boy, hell is going to be real crowded!” (laughter) C’mon man, give the people some breathing room. I’m very careful around religious people because I don’t want to offend them. But for me there’s life and death. And I live with urgency because I feel my body changing. It’s not what it was even five years ago. I think about some of these trips that I do and, “Okay, man I better bring a lot of aspirin.” Going out and walking around all day – I do a day of that now and I’m just in a lot of pain. It is what it is.”

JM: “Any upcoming photography trips planned?”

Henry Rollins: “I have this slideshow tour starting so by Christmas (2018) I’ll be in Reykjavik via Kiev, Ukraine and back in L.A. on the 25th of December if all goes according to plan. But as far as a trip where there’s not a stage waiting for me, I don’t know yet what 2019 is bringing. I’ve got a show that my manager and I and some other people are pitching, that we want someone to buy and let us go shoot. Once I get some hard dates of, “Here’s what you’re doing,” then I can plan travel around it. But I can’t book a travel I can’t get out of and then have to burn the tickets because I got work instead. By April or May of next year I’ll hopefully have some work that I can schedule around and then I’ll just pick some places I haven’t been to before, like New Guinea. I really like being in the Andes. I’d like to get up in the Andes again. I’ve only been to the Andes via Peru and Ecuador. I’d love to get back to Antarctica and South Georgia Island by way of Ushuaia. Everywhere I haven’t been interests me. Now, I’m ready for the slideshow tour. When I’m on tour I’m more at home. I don’t fear the stage. I’m prepared and I like my audience. I’m kind of looking forward to it. The weirdness is waiting to get out of here.”

—————- ——— — ——– —————-