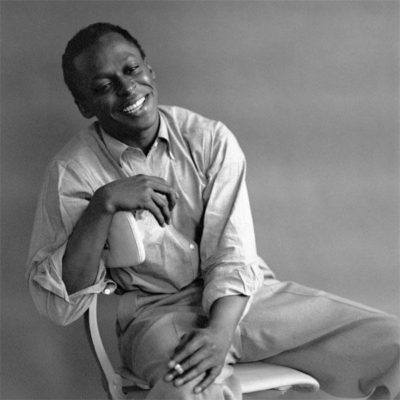

Post by DJ MoKat. Image by Tom Palumbo.

Everyone is so scared to make them. Mistakes, I mean. As students in class, we never raise our hands unless we are sure we have the right answer; even then, upon answering we search the faces of our teachers, our classmates for affirmation that we are correct when we speak. The common consensus stands that errors are bad, and so we refrain from making them.

Our pursuit of perfection is a lie that we know well. We have all heard that we are “only human,” and should therefore not expect perfect precision in our endeavors. The very phraseology of this expression attests to the observed inevitability of mistakes. As it applies to others, and when it is posed as a solely theoretical concept, this idiom is easily accepted and generally upheld. But as it applies to ourselves, we cannot accept that to be human is to be imperfect. We curse ourselves under our breath, flush red with embarrassment when we blunder, rush to immediately correct the wrong that we have committed the moment we discover it. It is another one of those very human paradoxes to know that mistakes are inevitable and yet to seek to eradicate them.

As new deejays, we have a definite fear of mistakes (we can each attest to the onset of heart-palpitations at the mere mention of our first air-check). But there is a case to be made for the benefits of errors. Because of their ubiquity, we find nothing more comforting than the presence of mistakes; they remind us that we are all human, validating our hopes of societal acceptance. Each mistake is a genuine moment of happenstance. In seizing these moments, we make art, enrich our lives, and we evolve. In no other medium is the positive power of the mistake more prevalent than that of the live performance – in our case – live radio.

Miles Davis put it best: “when you hit a wrong note, it’s the next things that make it good or bad.” This statement is remarkable for two reasons. One: a jazz god is admitting that he has experience with mistakes. Two: he does not denounce said mistakes. When listeners conjure up the image of a jazz musician, they see him from atop a pedestal. The term “virtuoso” has fallaciously become associated with flawlessness, much to the detriment of musicians and listeners alike. Although practicing with the intention of achieving perfection is key to virtuosity, true virtuosos come to a point where they realize that mistakes cannot be avoided, and thus must be willingly incorporated into their art. Doing so creates a strength of character and confidence as a musician, and adds a fresh dimension of vivacity to an artist’s music, as unforeseen musical possibilities present themselves. In being able to adapt to a mistake, one conquers the negative connotation associated with error and can then be more free to focus on expression, thereby allowed to make a truer piece of art. If “the emotional reaction is all that matters” as John Coltrane contends, is not an artist then making his work more meaningful by freeing up his attention to focus on the emotional content of his work, as opposed to the aesthetic appeal that many would associate with “perfect” music? Mistakes take on a new meaning when they are seen as an opportunity to create. An incomplete song can finish itself in unpredictable ways, a live performance can take listeners and performers alike down an unexpected path and lead all those present to a wonderful and unanticipated end.

On the surface, many would assume that the appeal of virtuosic genres such as jazz – or any art-form requiring honed technical skills – would lie said art-form’s faultlessness. Upon closer analysis, quite the opposite is true: we appreciate immensely technical works of art due to the expenditure of energy it takes to make them so near-flawless. Think: would the symmetrical tessellations of the Blue Mosque be so awe-inspiring if not for the knowledge of all the effort the stone mason must have put into his work? When we gaze at the designs, we don’t just see a beautiful motif; we see years of perspiration, careful attention to detail – all that which went into developing expertise. It seems it is only within the context of our errors that we measure our successes. We find work to be exemplary based off the degree to which a work’s creation is steeped in mistakes. Perseverance is beautiful, not perfection.

That being said, we learn best from mistakes. However, in school, we are rarely ever afforded the time to make mistakes. We realize their happening to our dismay, and then must learn new material. Our brain “alerts us in less than a second of an impending mistake so we don’t make it again.” We police ourselves with much greater efficacy than any instructor ever could, but we need time, repetition, and feedback from our instructors so as to take advantage of our brain’s self-correction system. To be better learners, we must first acknowledge that learning requires error. Furthermore, we must undo the emotional scarring associated with mistakes, so as to allow for better correction of them. When a student “feels stupid” after making a mistake, she generally tries to hide it, to deny its existence; a shortcoming that is enforced from above by the teacher, who does not wish to dwell on mistakes (as their student’s errors might reflect their own inadequacies). Despite the discovery of their students mistakes, teachers immediately move onward with course material, generally with an ambivalence toward poor scores. To the unconcerned teacher, mistakes represent laziness or lack of intelligence on behalf of the student; a sentiment which is inevitably absorbed into the psyche of students, leading to a negative feedback loop regarding mistakes and lack of improvement.

Although most students and teachers intuit the logic behind the necessity of mistakes (let us recall the ubiquitous use of “we are only human”) and science corroborates this understanding, the sentiment we carry regarding mistakes is just that: sentiment. We feel shame, we don’t think it. Being corrected for our mistakes feels like a personal attack, as though our intelligence is being insulted. However, regardless of how painful it may be at first, we must swallow our pride in order to learn. Not only do we have to be aware of our mistakes, but we have to be specific about them. “Knowing that answer #3 is wrong doesn’t mean much. Knowing that they didn’t understand mitosis gives them a mandate for getting better.” Knowing that you got something wrong is just the first step; learning how to fix your specific mistakes must follow their identification in order to improve. In letting students know that mistakes are fixable, that learning is a process, one makes success more feasible. We all stand a little straighter knowing that we are capable of success in the face of our inevitable blunders.

As deejays in training, it is important for us to take these last few paragraphs into account. Dead air, flubbing on a PSA or underwriting, clipping, playing the wrong track/entering the wrong track into Spinitron; a whole host of mistakes await us, or have already been committed. And in the live setting that we are throwing ourselves into, it is important that we understand both the inevitability and the power of our mistakes. There is a certain invincibility we have gained in the past few weeks on our mentors’ shows. There was only so much preparation we were allowed. Truthfully, nothing could prepare us in full for our first time on air. However, despite our sweaty palms and racing hearts, we got through our mistakes. Our mentors corrected us when we misstepped, and our breathing eventually slowed as we learned to embrace our mistakes so as to proceed on to becoming better deejays.

Here’s a secret: people listen to us because we mess up. If our listeners wanted perfection and predictability they would listen to Spotify or Pandora. Sixty-three percent of drivers still use traditional AM/FM stations as their main audio source. Why? In a sense, because we are all lonely. Humans crave other humans. It’s why we go to the mall even while we have Amazon at our fingertips. It’s why we go to parties. And it’s why we listen to radio. When a listener hears a deejay on air, they don’t hear a voice, they hear a person. Listeners are not drawn in by perfect enunciation and flawless segues. They are drawn in by a deejay’s humanity. And what is the cornerstone of our humanity? What makes us “only human”? You betcha. Mistakes. And if not overtly mistakes, the possibility of them proves to be enticing enough to both the deejays and the listeners.

As listeners, we love to feel included, as though the deejay is speaking right to us. Although faceless and known only by a pseudonym, radio deejays hold our attention by talking to us conversationally. Errors are abound: twisted tongues, flubbed lines, bad jokes, lost references, nervous laughs, careless sighs. These are inglorious signs of our humanity. This vulnerability is what draws listeners in and keeps them there. From a blunder comes the knowledge that the person on the other side of the transmitter is actually a person. You might be tempted to laugh out loud at their mistakes, and as you do so, you might find it easier to laugh at yourself. To accept their flaws, to see that their mistakes do not bring about the end of the world, – and by extension that yours will not do the same – is a blessing that no algorithm could ever bestow.

Computers make no mistakes. Computer scientists contend that “if you get a wrong answer, it is because you fed in wrong data or set up wrong parameters or calculations.” While this infallibility is comforting, it is not engaging. Computers make no mistakes, but as a result are confined by a strict set of limitations. Because of mankind’s ability to err, we can learn, expand our abilities; mix it up, so to speak. Although an algorithm can predict musical trends with great accuracy, it cannot guess what will make listeners happy. There is no code that provides that level of context; the parameters are not wide enough to accommodate something as abstract as happiness. But deejays can intuit the impact of their actions, and therefore successfully communicate with an audience, giving them the connection they actually desire. Listeners are not tuning in so as to experience an appropriate or logically sequenced playlist. They are listening for songs that make them feel connected, excited.

In order to draw an audience, a deejay must first be enthusiastic about their work. Despite our ardor, if the proper provisions are not taken deejaying can become monotonous and lead to boredom, which compromises the broadcast as a whole. Maintaining energy is key to maintaining an audience. Hence another silver-lining of mistakes: they keep us interesting. A study conducted by students at Emory supports the hypothesis that “‘the brain finds unexpected pleasures more rewarding than expected ones.’” To see a football player fumble with the ball only to make a spectacular recovery is certainly more entertaining than to see him complete the expected outcome (i.e. to catch the ball). The same applies to radio artists. Both listeners and the deejays themselves find the broadcast enriched by the presence of mistakes. When things go wrong, it is a test of a deejay’s adaptability and prowess to correct their untimely error in a timely manner. The first spike of the adrenaline rush initiated by fear of failure soon fades to the warm glow of self congratulation and perseverance. At no other point will a deejay feel more accomplished than when she has just avoided crisis.

The triumph associated with this moment is dynamic. In the event of dead air, audience members lean in, groping through the static for the voice of the deejay on the other side, anxiously awaiting the reformation of the connection they fear to be lost. But after a brief pause, a bit of “dead air” they are exultant, or in the least relieved at the recommencement of the program. At no other point will they appreciate the voice of the deejay or the power of the songs they play than after a moment of fearing they won’t get to hear them.

Although the FCC does not tolerate the occurrence of mistakes, it makes provisions for them in the event that they occur (disclaimers read after accidental use of profanity, etc). The existence of said provisions attests to the FCC’s uneasy acceptance of the fact that radio deejays are human. The irony that a large bureaucratic organization so removed from the actual production of radio art (being consumed with its regulation) so readily accepts one of the most intimate truths of human production while the individuals that produce the art remain adverse to it is bewildering. It seems in all contexts except those that apply to our own actions, we can forgive mistakes, even celebrate them. As our current adversity to mistakes still stands, we make our jobs more difficult for ourselves by fearing the inevitable, and at times may handicap ourselves from fear of failure. But this failure is temporary. Mistakes do not define our work, but rather force it and us to grow.

The very nature of radio is imperfect. The range of our transmitter fluctuates. The vinyl and CD’s we play music from are prone to scratching and skipping. Equipment must be calibrated, re-calibrated, and tested to ensure that it works. We stutter. Our hands slip. We misspeak. If art is an accurate reflection of our humanity, than our mistakes are but a genuine facet of our capabilities. We have been taught by prior experience (in school and other social settings) that mistakes are the bane of our existence. But what if they are the crux? Although we have the illusion of control over the airwaves given to us by the impressive presence of the soundboard, there are still variables beyond our control within our medium. And I would argue that those are some of the most exciting elements of radio. To harness the power of the unexpected, and thereby pass it on to others through our artform, we deejays come as close to invincible as any humans can be – but we are forever far from flawless.