By John Malkin

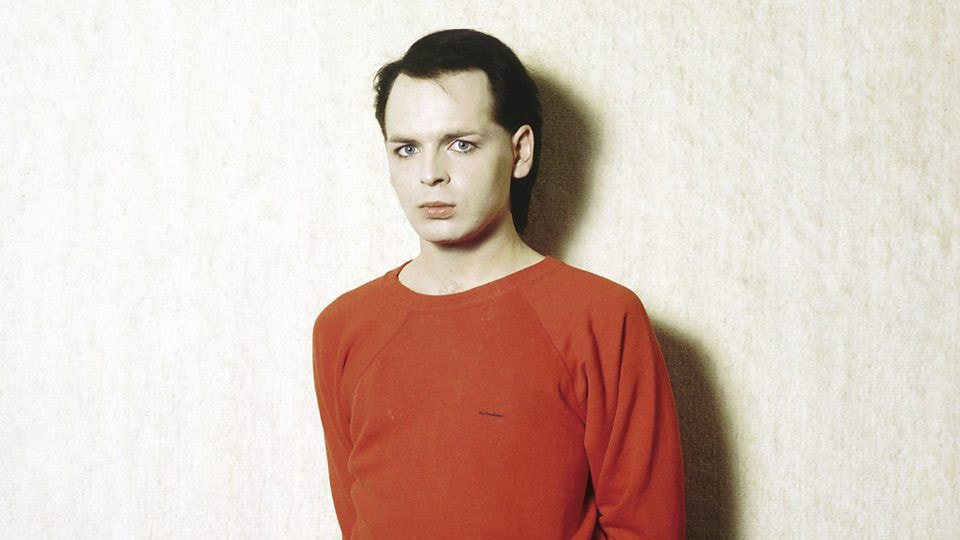

Gary Numan has had an extraordinary musical career spanning almost five decades. He rode the first wave of British punk into developing electronic-synth rock fused with science fiction themes. Numan had two worldwide hits in 1979 with “Are Friends Electric?” and “Cars” which he’s said was, “probably the happiest song I ever wrote. And it was about road rage.”

Numan just released his twenty-first studio album – Intruder – and is preparing for a 2022 tour that will take him across Europe and the U.S. including gigs at San Francisco’s Fillmore on February 24th and The Catalyst in Santa Cruz on April 3. Numan has spoken openly of his struggles with anxiety, depression and Asperger’s, a syndrome characterized by repetitive, obsessive patterns that he believes has benefited his creative focus and drive.

This interview was originally broadcast on “Transformation Highway” with John Malkin on June 14, 2021 on KZSC 88.1 FM / kzsc.org.

INVENTIVENESS AND CREATIVITY

JM: “Would you start off telling me about your new album Intruder? I know sometimes your songs come from what you’re taking in around you. The conversations, films, ideas that are floating around. But it sounds like you’ve also been writing over the years. I’m wondering if you’re going to write a science fiction novel at some point? But tell me more about your process and how this album came together. And also, what it has to do with the world we’re living in; the climate crisis and social crises that are happening.”

Gary Numan: “As far as process is concerned, I’m not really aware of having one. Honest to god. When I say, “Right. I’m going to start the next album Monday…” – And I am actually going to start the next album Monday! So, Monday comes along. And I go out there and I turn it all on and I sit down at a keyboard. And I just start and see what happens.

Coming up with tunes, coming up with melodies, I can do that all day. I can do dozens and dozens every day. That’s not the problem. Finding the ones that work, the ones that you can make into something else; that’s just a decision. Decisions you make as you go along. That works. And that works. The more difficult stuff comes after that, when you start to add layers and complexity to it. The tune in a way is sort of like the skeleton – it’s the solid framework that everything else is wrapped around. And the way you wrap it can make a huge difference as to what that song ends up being. But the core of it will always be the melody. Everything starts with that. So, I suppose that’s a process. It all starts with that.

And then I start to build up the music, long before I send it over to Ade Fenton who produces my stuff. I produce it myself up to a fairly complete level. Not with any intention of that level getting out, but to give Ade as much guidance as possible. As to where I hear the song going; the dynamics of it, the light and shade of it, the feel of it.

But the lyrics tend to be the last thing that I do. Because I feel that the lyrics should be guided by the mood of the song. That the mood of the song, the music that you’ve made, will put you in a place. It will put you emotionally in a place. And the words that suit that will therefore flow more naturally, because you’re already in the place that the song is describing. You’re already immersed in that environment, if you like, and certain words and lines and even what it can be about at all, come to mind then. So, when I’m sitting down and writing a tune, I have no idea of a title, no idea what the lyrics are going to be about. And no idea what the song itself is going to be about. None of that at all. So, it almost makes itself by; everything you do is designed to trigger the next bit that you need to do. I often describe it as kind of a stumbling forward kind of process. Which is why I don’t think I have a process. If that makes any sense.

I can’t speak for all creative people but I tend to believe that it applies to pretty much everybody, is that we are very sponge-like, and so we soak up everything that’s around us. Most of my music is not influenced by other music because I don’t actually listen to music often at all. But I watch films a lot, I watch TV. You’re having conversations all the time, reading books, looking at photographs or paintings. You know, the world is absolutely overwhelming you at any moment with things. And it’s all going in. And that sponge is getting fuller and fuller and fuller.

When you sit down to make an album and you start to think about lyrics you just kind of give that sponge a squeeze and all that stuff just comes out. And it’s all mixed and merged together. And you’ve got no idea where most of it comes from. But it’s all in there. And hopefully what’s happened is, it’s merged with your own stuff that’s in there. I think your own inventiveness and creativity is also seeping into that sponge. So, it all just gets mixed up. The worry is that when you do things something will come out that is reminiscent of something you might have heard or seen, and you don’t recognize that. And you might unwittingly copy something or repeat something. I don’t think I have. But there’s always a risk.

I do remember many, many years ago I was working on a song. This would be the late ‘90s. I was working on a song and really thought I’d come up with a blindingly good chorus. I was really happy with it. And I called up to my wife and said, “You’ve got to come listen to this. I’m really happy with this.” And she said, “I’ve just been playing that! That’s Siouxsie and the Banshees!” I went, “Fuck off! Fuck off!” I said, “Really?” I hadn’t realized it but she’d been playing it upstairs! And I’d obviously been hearing it, but not really registering. And I just said, “Oh, that’s just great, that.” And thank god she told me! That would have been hideously embarrassing! So, it can bite you sometimes. But generally speaking, that’s just the way it is for me.”

.

MUSIC HAS BEEN LIFESAVING

JM: “It really resonates for me, this description of a sponge. I play the piano. And long ago I started thinking of the piano as an emotion machine. It’s like all the stuff that comes into me, I really want to get it out to so I’ve picked music as one of my ways to do it. I don’t know if you feel the need to get stuff out and that music is your way to do it?”

Gary Numan: “It is. It is a need. I’ve often described music for me as being more of a need than a job. More of a need than a hobby even. And it has been very useful. That ability to get things out has been almost life-saving at times. As an example, my wife had postnatal depression after our second baby that drifted into the third. By the time the third one was born she was in a terrible state. And I was dealing with that and it was very difficult. And then for various reasons, I then got diagnosed with depression. So, we had this long period of several years where both of us were not in a really good place and not getting on the way we used to. It was very difficult. And at one point, I was thinking about leaving. And so was she, although I didn’t know that at the time. And I went outside and started to write a song called “Lost” which is on the Splinter album, two albums back. And in the course of writing anything, you obviously think very, very deeply about it because the words you’re going to use are very important. And you want to make sure that they’re accurate and convey exactly what it is that you’re feeling and thinking.

So, I started to write this song “Lost” and it reminded me of all the things that I loved about her that I’d forgotten. I think the problem when you stop getting on with somebody, even though it’s only for a very short period of time, you only remember the last argument. You just remember the last things that were said and you dwell on them. It becomes that all your memories of that person are bitter, because you’re just remembering the argument. And I think that happens to all of us.

By being able to write, I was able to remember – and I didn’t intend that to happen, it just happened – all of the other things. The things that I’d forgotten, the things that had been blurred, if you like, by the arguing. They were all there, everything that was amazing about her was all just laid out. And it was an amazing thing. And I wrote the song and I went back in and I apologized for everything that I’d said, forgetting how amazing she was. And that was the last time we ever argued. I think. And everything was fixed. And it did the same for her. By me doing that, it just wiped away all of that bitterness. And she remembered all the good things about me that she had liked before, and it just fixed everything. And if I hadn’t been able to write songs, if I hadn’t had that skill, if you like, of being able to go deep inside and get all these things out, then we probably wouldn’t be married now. And my life would be totally different.

So, it’s more than a need, even. It’s an essential part of who I am and how I deal with the world and how I cope with the ups and downs of existing. Being able to write is an amazing thing; it gets rid of all of my tensions and worries. Which there are many, as they are for all of us. But I am able to get them out. So, I remain – it’s not quite the right way of putting it, but – sort of level. You know, I get wound up and I get angry and all of those things and I’m quite highly strung at times, and yet to be able to write it all out is like having a valve. You can just let it go like a cartoon character with steam coming out of their head! It’s a bit like that. But not just steam, it’s much more than that. But it’s been proven to be an incredibly helpful thing for me to get me through life and not sort of be bouncing off the walls all the time.”

HARDCORE ATHIEST

JM: “There’s a song on the new album called “When You Fall” and the words struck me strongest on the whole album. You’re singing, “I want to talk about your thoughts and prayers. I want to talk about your god. I want to talk about the things we share. Is there anything?” I’ve heard that you’re an atheist and I share all these sentiments, too. Religion is bizarre; the teachings and people that religions are based on emphasize compassion and love, especially towards people who think differently than you. And look what religion has done with that; terrible genocides and violence. And there’s this other part of religion, or spirituality, that you’re sort of talking about. Part of it is being kind to yourself and others when you’re stumbling. Some people say they never stumble, and maybe a lot of rock stars look like they’re not stumbling. But you’re talking – and I’ve heard you talk about this quite a bit over the years – about stumbling forward. And I have viewed my life that way, too. I think most of us do. There was book by Samuel Beckett – “Worstword Ho” (1983) – which I must have read around the time I started hearing your music and punk rock. And there’s a short sentence in this book, “fail better.” I’ve always considered that and when I encountered Buddhism around the same time, I found that this is a big part of Buddhism. Paying attention to what’s happening, even if it’s stumbling, and loving that. I don’t know if you would say something about that song and organized religion. And then these other qualities of being able to love the stumbling.”

Gary Numan: “As far as loving stumbling is concerned, I’ve always believed that we are shaped, more than anything, by the way we deal with adversity. It’s the disappointments, setbacks and losses that we have to endure that do far more to shape the people that we become, then all the good experiences. We tend to take good news and advancement and good things in general, we seem to take them very much in our stride. You carry on and we are much the same people as we were before, slightly more arrogant perhaps, depending on what’s happened, but much the same as before. But people can easily be crushed or twisted in quite unfortunate ways by adversity. And that’s what I mean, by the way we are shaped by it.

If you’ve had lots of setbacks and disappointments and loss, or whatever would count as negative things. If you come through that, and at the end of it all you’re still a kind, decent and generous human being, then it shows a great deal of moral character. A great deal of humanity. And if you’ve got someone that’s led a charmed life, and at the end of it is a pretty good bloke, well, I’d expect you to be, really. But if you’ve had lots of ups and downs in your life, for all of the amazing highs that you might have had, you’ve had plenty of lows as well, and you come out the end of that and you’re still a pretty decent person then I think more credit to you. Because there are plenty of people that would not end up that way. They can become bitter and greedy and feel the world owed them something and they didn’t get it. You just feel angry with the world and people in general and become drunks or a druggy or whatever. People are very easily destroyed, it seems to me, because they think they deserve more than they get. Rightly or wrongly.

The religion side of it. There are endless examples to me of where religion does not live up to the words that it preaches. I’m so sick and tired of seeing scripture quoted by normal people, or even more frustrating when you see it spouted by political figures. You know, the scripture of the day. And they live up to none of it. Absolutely none of it. Even the Bible – certainly the Old Testament – is full of examples of cruelty and the symbolism of devotion and so on.

Looking at nature itself; if this is considered to be a God-given system, its unbelievably cruel and savage. Most things eat other things to survive. God’s answer, apparently, to overpopulation is to create a creature with big teeth that will eat lots of you so that you don’t overpopulate. How is that any kind of answer? In this world supposedly created by this all-kind and all-forgiving deity. It’s just bollocks! I could go on for the rest of the day on this. I’m hardcore atheist, obviously. I find much of it to be frustrating.

On the other hand, though, having said that, I remember very well when I was very young a friend of my father’s was killed in a car crash and his mother got a huge amount of comfort from her faith. She would go to church, she would pray. She would genuinely believe she was communicating with her son and it made what remained of her life less painful than it otherwise would be. Still painful, but she honestly believed. So, in that sense, her having faith gave her a comfort. I have nothing but respect for that. If that’s what you get from it, then good luck to you. It’s the hypocrisy, the double standards that come with so much of it. The majority of it to me seems to be double dealing, left, right and center. Holding up a placard saying one thing, when back home you’re doing something completely different. You know, talking about loving your neighbor at the same time as you spit on your neighbor. Or because your neighbor is Black, you won’t help him or whatever. A million and one things it’s the hypocrisy. It’s the bare faced lie of it, that people can stand there and say all these things knowing that they are not living it.

And the corruptibility of the word. The corruptibility of the interpretation of what it says, people are able to twist pretty much any sentence in the Bible to make it suit whatever they want, to justify what they’re doing at that particular moment. And not see the hypocrisy or the bullshit of that. And they still believe they’re devout and a good Christian person, when anyone with half-a-brain sees they’re clearly nothing of the sort! And yet they feel righteous. And that righteousness makes them look down on other people, which surely is the last thing that any Christian should do, to look down on anybody else whatsoever. I have no time for it. For any of it. I’m a good person because I know what being a good person means. Not because some fucking book tells you what the rules are!”

THIN LAYER OF CIVILITY

JM: “I have a thirteen-year-old son and I know you have three kids. Sometimes I’m a little sad about the world I’ve brought him into. We’re facing a lot of difficulties, which isn’t new. We grew up hearing, “Hey, things need to change.” And even with this idea that, ‘Wow, a nuclear war could happen at any moment.” We lived with that. And the present pandemic has this odd feeling like a war is going on, in a little bit of a way. You know, having to be worried about going outside and you have to wear a mask. And maybe you can’t find things. At least a year ago when it started, it was like “Are we going to do without certain things?” The pandemic has been pretty profound.

In some ways, your music and performance has always had something to do with taking a look at where we’re headed. The development of machines, cyborgs, robotics, technology. And at the same time, you’re using some of that stuff to make your music. I thought it was kind of funny and interesting; I’ve heard you describe the song “Cars” saying it’s probably your happiest song, and it was about road rage.

With screens we’re able to talk to each other. And for making music, digital technology is amazing. But I’m a little worried how we’ve taken pretty huge leaps forward in getting stuck on screens during the pandemic. And it’s sort of what we have to do right now. But it might remain with human beings. And it causes a lot of separation, too. I wonder what you’re thinking about hope, or lack of hope? And the development of technologies? I can also just say, it looks to me like a lot of people are hoping science and technology are going to get us out of our problems. I’m not so sure that that’s true. Nature is a lot bigger than all of that.”

Gary Numan: “I’ve come to believe, during the course of making Intruder – and my wife has said, ever since I’ve known my wife – she says all we need to do is get rid of everybody, kill everybody. And the world’s a happy place. That’s not entirely true, because everything is still going to eat everything else. But I know what she means. But I’ve always argued against that. The world has got a huge amount of lovely people. There’s lots of bad ones and lots of ignorance and stupidity. But I believed that essentially the majority of people are good and decent people. I feel less confident about that actually now. That’s partly because of the last four years. (Donald Trump’s presidency, 2017 – 2021) The last four years seemed to have scraped off this thin layer of civility that had me fooled completely, coming from more of an American point of view. I have been living here now for a long time and I’ve got my American citizenship now. So, I feel I’m allowed to say this, and it’s not a criticism. But my impression of America was of a far more tolerant and all-encompassing country then it turned out to be. And it seemed it only needed one unpleasant figurehead to come to power for that thin layer to just be peeled away. And to see all that hostility and resentment and just unpleasant feelings, really, that were sort of lurking just below the surface. I feel like it’s not just put us back four years. It feels to me like it’s put us back a generation or two in some respects, which has been disappointing. That’s the thing that, for me, the pandemic highlighted more than anything else; this division. I think that’s going take a while. I don’t know that we’ll ever… We should obviously never forget what’s happened. And I do think it made a lot of things very, very nakedly visible. So, there will hopefully be a greater emphasis to do something about that, and fix things.

But it really did highlight a huge amount of unpleasantness that seemed under the surface. I know I’m European coming here, and things there are not perfect by any means. I do have an American-European slant on this particular issue. It seemed to me like a certain amount of unraveling of decency, which was shocking for me to see. Unashamed, out in the front, screaming at you in the face. I don’t know how anyone can be proud of that. How anyone can be that and somehow think it’s good? It’s almost like the gang mentality; you get ten, twenty, thirty people together and they would do things they would never dream of doing on their own. They wind each other up. Your barriers as to what’s acceptable and what isn’t, is fluid. And they move depending on how certain elements in that group can fire you up to do unthinkable things. That seems to have been done here on a massive scale.

So, I’m very torn at the minute as to whether people are going to go back to, “Fuck! What on earth made me do that? That’s not really who I am.” And they come back to that sort of level of decency, again, that we would all wish to see. Or they really are just like that, and all it needed was someone just to say, “Come on, do it. Do it.” And they do it because they really actually don’t care. They want to do that.

In a way the song “When You Fall” hints into some of that. The whole “thoughts and prayers” thing! Every time there’s another shooting, mass shooting. If fucking Ted Cruz says he offers his thoughts and prayers again I could punch him! “Really? Thanks. I’m incredibly grateful, Ted, for the time you spend with your thoughts and your prayers. Meanwhile, help carry the fucking bodies away, you cunt. Fucking hell.” I find it very frustrating and the fact that they stay in office. Which means they have supporters; there are people that believe what they’re saying who can’t see through the bullshit of it.”

BULLDOZER OF A SOUND

JM: “Yeah, I feel the same. I am still blown away that roughly half the country voted for that last guy. I cannot I cannot make sense of that still. And I think, potentially, through the pandemic, there could be changes that happen. I’ve never heard so many people around the world say, “We need to stop how police do things. We need actual community safety.” And I’ve never heard so many people re-examining history, of even just the United States. This country is grounded in violence and genocide, brutality, slavery. When before people looked at those things as blemishes on a positive history.

And I want to ask you about punk rock. In a way, this is a perfect segway. Partly what drew me to punk rock in 1978 or ‘79 was that, things are in some ways worse now. But things were already bad then, with the leadership of the United States and constant warfare. So punk rock people were singing about that, and doing something with their anger. And at the same time there was really interesting electronic music happening all over the world. In 1981 the movie “Urgh! A Music War” came out and it was inspiring! You’re in there with Gang of Four, Dead Kennedys, Au Pairs, Skafish, XTC, Joan Jett; a pretty broad, weird, compelling group of musicians. I’m not sure if your first music making was punk rock. And I’m not sure if that was a band called The Lasers. Or if Tubeway Army was your first? Tell me a little about what was compelling about punk rock and your first forays into it?”

Gary Numan: “I was in a band before The Lasers and Tubeway Army. I was in a band and we only did three shows and each time we did a show we had a different band name. Because nobody could decide. So, I realized very early on that being in a band involved compromise. And I wasn’t really interested in that too much. But then I got thrown out of that band, ultimately. I got thrown out because I wrote all the songs. I said, “Well, what songs have you got then?” And they didn’t have any. “Well, alright?”

So, I decided that I would join a band called The Lasers. And I’ll just stay in the background. That would be my deal; just stay in the background, be in a band, get some experience. Not try to sort of insert yourself into any sort of position within it. Just enjoy being in a band for a little bit and find out what it’s all about and gig around London. So, I did the audition and got in the band called The Lasers. The first rehearsal was at my mum and dad’s house, actually. We were playing for a bit and I said, “You’re only doing cover versions. Every song we’re playing is a cover version.” And I said, “Why is that?” They said, “Well, we don’t write songs.” And I said, “I do. I’ve got loads.” So, I played them some of my songs and they said, “Oh, they’re great. We’ll do them.” So, we started doing my songs.

The singer in the band was also the bass player, Paul. He said, “I can’t sing them, they’re not in my range.” So, I ended up being the singer as well. This was all at the first rehearsal ever. And at the end of it, I said, “You’re called THE Lasers.” And they said, “What’s wrong with that?” I said, “Well everyone’s called THE something. Everyone. THE Clash, THE Sex Pistols.” I said, “We need something a bit more interesting. And they said, “Well, what do you suggest?” I said, “Well, I’m writing stories. One of the chapters in the books I’m writing is called “Tubeway Army.” So, at the end of that first rehearsal, they were now doing all my songs, I was the singer and I changed the band name to Tubeway Army.

And I still don’t think I was being pushy. I really wasn’t trying to push myself on them. I was just talking, because I was so interested and passionate about the whole thing. I wanted to be a part of it. It just worked out that way. I didn’t go into that rehearsal with the intention of changing the music and changing the band. It was just a conversation that ended up being what it was. I think it’s true in a great many bands that the majority of people in them are just there for the laugh, really. They’re just there to have fun. But most bands will have someone in them that’s driven, that thinks about it. Has thought about all their life and is a fountain of ideas. So, that was me in that particular band.

The whole punk rock side of it; I found it really exciting to begin with. I remember going to see Sex Pistols when they did a gig in a club in London called Notre Dame. This was before the dreaded TV show that got them into so much trouble. I remember going to see the Clash when they were doing support in a little bar somewhere. So, I was in there, I was right at the front end of it when it was all going on. And going up and down Kings Road and hanging out with those people. I remember talking to Sid Vicious before he died. Only briefly, and I didn’t know him very well. So, I was a part of it.

I did find it very, very exciting. But I never thought it was for me. So, I joined a punk band and I developed Tubeway Army as a punk band. Not because I was passionate about the music, and not because I thought punk rock had something long lasting or meaningful to offer. It was because I saw it as an opportunity. I saw punk rock created a re-evaluation of what music was about, what it was there for. Why it was not to be taken so seriously and so earnestly. It was just; go out and say what the fuck you want! And do what you want, and just rip the shit up while you can. That’s what this is all about! That’s what music should be about. Lots of young people getting out and just being mental and having some fun with it. And I loved that side of it. But that’s never going to last. You know, that’s going to be a moment in time.

And that moment, I noticed, was creating… it was as if a whole load of doors suddenly appeared on a wall that had been firmly in your way before. There was no way through that wall apart from a major record company there, a massive independent there, who were very arrogant and very selective and very difficult to get into. All of a sudden that wall suddenly had a dozen doors in it – big ones – and you opened that door and behind it was half a dozen little punk labels. Suddenly there was lots of opportunity. Not to go a long way, but to get your foot on the ladder. Whereas before, you couldn’t even see the ladder. It was just not available to you. And that’s what I noticed. So that’s why punk for me became a vehicle to somewhere. I knew I didn’t want to do that long term. I knew I didn’t want to do that much more than short term. But it was a doorway to somewhere. I just didn’t know where somewhere was going to be.

That’s why the electronic thing for me was just luck. Absolute luck. I had no intention of getting into electronic music. I’d heard Kraftwerk and liked it. but not enough to turn me on to it. I heard some of the Bowie stuff, the Low album – I really liked it, but I didn’t want to do it. It didn’t excite me enough to want to do that sort of music. I was still very much guitar-based.

But then I went to a studio to record our first punk album, having got the deal with Beggars Banquet. And the synthesizer was there, it was just sitting in the corner of the room. Never seen a real one before. I’d always been a bit geeky for technology, so I thought, “Look at that, man. It’s just covered in dials and switches and buttons and shit.” It looked so cool. Like Starship Enterprise in a box. It was amazing! So, they let me have a go of it, you know, while the other two are unloading the guitars and amps and putting them into the studio and a drum kit. I’m in the control room with the studio engineer. And he turned it on and said I could have a go. And I just pressed down one key. I had no idea how to set them up. So, I just pressed a key and waited. And it was just awesome. It was the heaviest, hugest bulldozer of a sound. The whole room was shaking. Fucking hell! I just never heard anything like it. And I thought, “That’s me. I’m done. That machine, that thing there, that can do more than all of this stuff you’re unloading. You hold that key down and turn that and it’s a totally different thing.” There was nothing else like it, nothing else like it at all.

In that moment I was absolutely sold on it. And convinced that this was the future. This was coming. And I didn’t realize at that point how many other people were actually doing it. I thought that was one of the very first to discover it in that way. I knew that Kraftwerk had been doing their very sort of robotic, fully synthetic music, which is cool. The Bowie/Eno thing which was more grandiose, almost classical music, but electronic. I knew it was out there, but I never heard anyone sort of make rock music with it. But it was out there. I just hadn’t heard it; that was my ignorance. But I thought it was amazing. And I did think it was the future.

So, I recorded the album using that synth. It was very much a hastily… everything was adapted, kind on the fly. I’d take guitar parts out and put the synth part in. I didn’t know how to set it up, so I twiddled for ages until it made a noise that I liked, and then quickly record it. I went back to the record company with that record, which is not what they wanted at all! And then got into a massive argument with them. I tried to convince them that this was the future, this machine, this sort of music, is surely what’s coming. I said, “We have the chance to be right at the front end of something. This is going to change everything. You can be, right now, on a spearhead of what’s coming. Or you can try to force me to go make a punk album, which anyone can see is already on its way out.” It was already finished. This is ’78. Punk was over in ’77. It all peaked in ’77, in Britain anyway. And it just faded away. So, “This is what’s coming. But this has the same attitude that punk had. This is different and this is a new way of doing something.” It articulated, in a way, the same message that punk had. But it’s an entirely different thing. “Listen to it. There is nothing like this at the moment. This is what’s coming,” so I thought anyway. And after a long argument and very heated one at times. But I was really young.

But they agreed to it. Ultimately, they said, “Alright, we’ll put it out.” And it didn’t set the world on fire, it wasn’t great. But it didn’t get slaughtered the way they thought it would. So, they let me make another album. I made three albums in eleven months. That was first and the next one was Replicas, then Pleasure Principle. All within eleven months, so I was flying. The next one, which came out five months later than Replicas that had “Are Friends Electric” on it and “Down in the Park,” and that was number one. So almost immediately it went from this weird little thing that I was having to fight for, to this number one thing. And then everyone’s trying to sign their electronic band and all the major labels want an electronic band. The whole thing just took off. And it became a genre in its own right.

I honestly believe that it was probably the last true revolution in music. I think everything since then has been an evolution of that moment So, I’m really proud to have been a part of it. And I really was just a part of it. There were people like Human League and OMD. And Daniel Miller who went on to do Mute (Records). These people were already out there. Ultravox, especially the early Ultravox with John Foxx, they were doing it long before I was. They were genuinely groundbreaking. They just hadn’t had any success.

So, I come along and had all the success and stole their thunder a little bit. But a lot of the credit I get, I think is largely undeserved because I was near the front but I wasn’t quite at the tip of the spear that I thought I was. I was just a little bit further down it. They were the tip of the spear. Ultravox had made three albums by the time I made my first one. And they were much more accomplished than I was. They just didn’t put it together the way I did. I think that’s where it’s different. I got the whole; the image, the presentation, the lyrical content. I was the whole package in a way and the music just being a part of that. And I think that’s why I took off. And I had the luck to be in the right place at the right time with just the right amount of experimentalism, just the right amount of conventional sound to it. It was an accidental mix that worked at the right time.

I’d seen Ultravox on TV six months before, or a year before me, I can’t remember now. And I remember I said to my mate – Paul Gardiner – at the time, who was in the band, I said, “Look at that. They got this great music. But it don’t look right. It don’t look the way the music sort of says they should look. They’re singing about Hiroshima and he’s got a fucking Hawaiian shirt on!” You know? All the pieces had not come together properly. Everything has to do that. It has to fit. Everything. The way you look, the way you sing, the way you move, the way you talk. The music itself, obviously, the lyrical content. Everything needs to complement everything else. It’s a machine and all the pieces of that machine have to work together in some sort of harmonious fashion for it to work. And they hadn’t quite got their gears in order at that point. And I did. And I think that’s why I sort of took off before them and stole their thunder somewhat. But I’m very keen to make the point that they were there before me. And they were better. They were better than I was. I think.”

JM: “I loved Ultravox. Maybe in 1982 I saw them in Pasadena. And they came to this little record store down here in Orange County. And I took my snare drum there to have the drummer sign my snare drum! (laugh) Yeah, they were great. I thank you for giving me time today. It’s really been very delightful to spend time with you. And I’m so excited that you’re going to start a new album on Monday. When it comes out, I’m going to listen carefully to see if there’s the melody from “Hong Kong Garden” by Siouxsie and the Banshees! (laugh)

Gary Numan: “You never know! (laugh) Thank you.”