Interview with Vieux Farka Touré – May 11, 2022 – “Transformation Highway” with John Malkin – KZSC 88.1 FM / kzsc.org

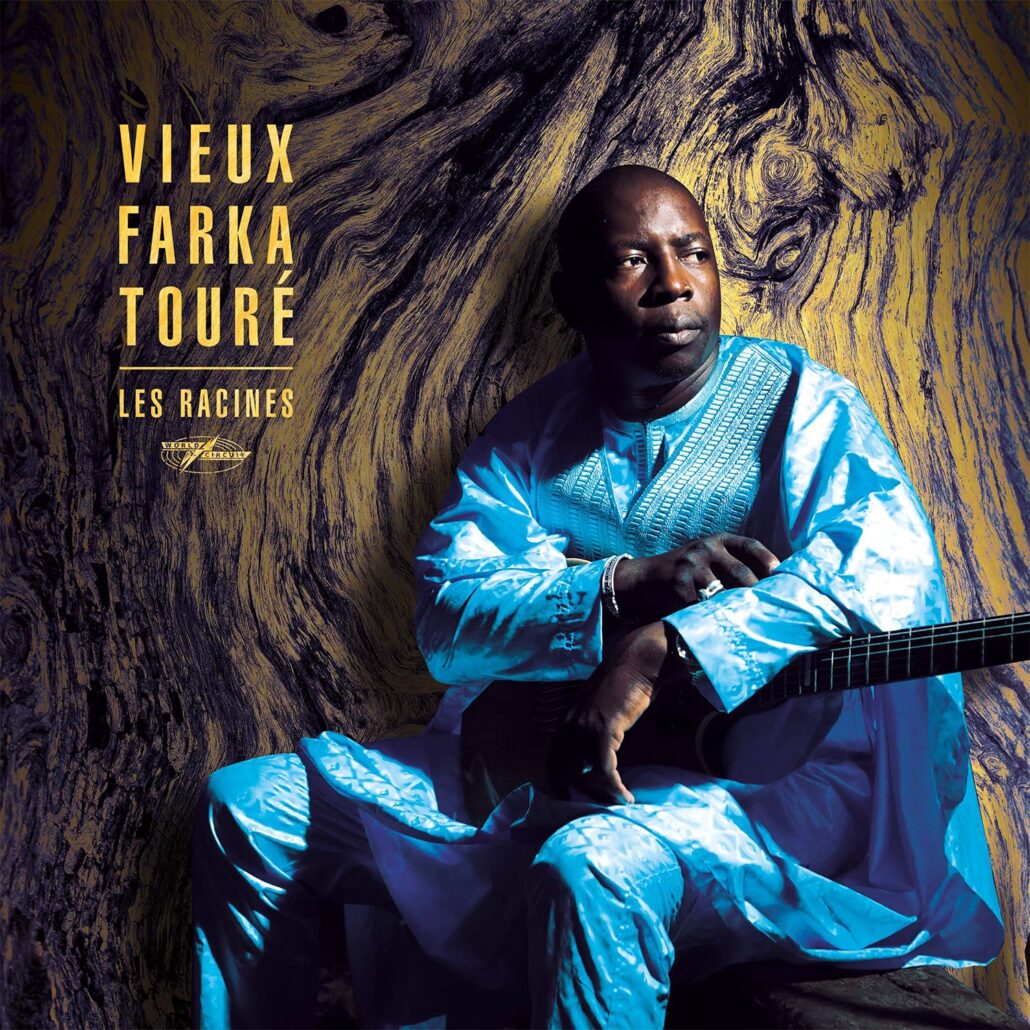

AFRICAN ROOTS OF THE BLUES: Vieux Farka Touré Releases “Les Racines” and Plays Felton Music Hall

By John Malkin

African Blues guitarist/vocalist Vieux Farka Touré performs this Sunday, May 15th at 8PM at Felton Music Hall, including songs from his new album Les Racines which translates as “The Roots.” The album is set for release by World Circuit Records on June 10th. It’s Vieux’s fifth studio album and is a whole-hearted reconnection with the Songhai music of Mali, one of northern West Africa’s musical traditions known in the West by the catch-all term “Desert Blues.”

Vieux Farka Touré recorded Les Racines in Bamako, Mali in his home studio, which he built just before the Covid-19 pandemic caused shutdowns across Africa and the world in early 2020. Vieux named the studio after his father, eminent African Blues guitarist Ali Farka Touré, who passed away in 2006. Vieux explains in the album notes; “It’s important to me and to Malian people that we stay connected to our roots and our history.” He adds; “It’s difficult to be the child of someone who has gone to the top of the mountain. The album is an homage to my father but, just as importantly, to everything he represented and stood for.”

The rhythms and melodies of Les Racines are exciting and complex, interlocking in surprising and exhilarating ways. Vieux’s guitar dexterity and groove are masterful and he invited a remarkable group of African musicians to participate in recording the album including Madou Traore on flute, Kandia Fa on ngoni, Souleymane Kane on calabash and Toumani Diabaté’s younger brother Madou Sidiki Diabaté playing kora. Cheick Tidiane Seck adds incredible keyboards and Amadou Bagayoko, from Amadou & Mariam, adds guitar. Vieux was born in 1981 in Mali and took up guitar even though his father discouraged him from entering the “bureaucracy of professional music.” Vieux Farka Touré has collaborated with Dave Matthews and jazz guitarist John Scofield as well as Israeli keyboardist Idan Raichel as The Touré-Raichel Collective. He’s the subject of a new documentary titled “Vieux de Niafunké” by director Ian Campbell. The Sentinel recently spoke with Vieux Farka Touré and his manager/bass player Marshall Henry about returning to traditional African music.

“GOING BACK HOME” MUSIC

Q: “Why was it important for you make an album of traditional music from Mali?”

Vieux: “It’s been a long time that I’ve been making my own music, because I have to create my own role. I’ve wanted people to know, “Okay, this is what we have from Vieux.” But the music I’m making now is very similar to my father’s music. This is going back home music,” says Vieux. “When I started playing music, my father already had Grammy Awards for his music. He was the top level at what he was doing. I said, “He is already at the top, so if I take this road, I have to do something new. Something we can call Vieux Farka Touré.” I’ve recorded for sixteen years since my first album in 2006 and everybody knows my style. Now I’m going back to the roots of West African music. I’m going back to my home, to embrace the traditional Songhai music of Mali.”

Q: “You have amazing musicians on this album and the rhythms interlock in complicated and interesting ways. Twos and threes are played together and the song can be approached in both ways, depending on how you listen to it.”

Vieux: “Yeah, it’s difficult. But this is what I’m used to. These are the rhythms I grew up with. I think I have this music in my blood, you know?” asks Vieux rhetorically. “Souleymane Kane is on Les Racines and he played calabash (percussion) with my father. I wanted to bring musicians from Northern Mali to create this traditional album and I invited people like keyboardist Cheick Tidiane Seck. To make this traditional music you have to be very skilled because it’s complex. I don’t say it’s my music; it’s my father’s music. It’s the soul of Mali and you have to be very special to play this music.”

GUITAR LESSONS IN THE NIGHT

Q: “I read that your father discouraged you from going into the music business.”

Vieux: “I didn’t tell him when I started to learn guitar. I remember when I was first playing guitar, one of his friends told me, “Your father listens to you by the window when you play.” I said “What? He’s there?” He said, “Yeah, he’s standing there for twenty minutes. Listening to you play the guitar.” My father didn’t want me to be a musician because of the bureaucracy of the music world.

People maybe don’t know that my father never went to school. He never read the contracts that he signed as a musician. He didn’t read anything. They were going to give him money and he signed, but he didn’t know what he signed and he had many problems. That happened until he signed with Nick Gold and World Circuit Records. That’s why he always told me, “No, music is not good.” But it’s not the music! It’s the people working in the music world.”

Vieux continued, “My father did start to teach me a little guitar. He sometimes listened when I played the guitar and then I think he knew, “I don’t have a choice. I have to give Vieux some lessons.” So, he started giving me lessons in the night. Just him and me, playing. It’s crazy because every night we would play for thirty minutes or one hour and every lesson felt like two or three years! I started to learn the guitar in 2001 in The Institute of Art in Mali. In 2005 I recorded my first album and people said, “How can you play the guitar like this in four years?” I think it’s because I had a good teacher.”

Q: “I’m glad you had the chance to learn from your father. It sounds like every lesson was a journey. How did it go recording Les Racines during the pandemic?”

Vieux: “I was already planning to record this album, before the pandemic. I wanted to make an album like my father’s music,” Vieux told the Sentinel. “It was good to build my own recording studio finally because it’s sometimes a little bit difficult to have to work like this; every time you call the guys from the studio they say, “Ah, we don’t have time. Wait for tomorrow.” I thought “Okay, I want to build my own studio. I have space.” I said “Marshall, what are we going to do? I need to put half of my money to build the studio.” We started to do the studio and we finished making the studio at the beginning of the Covid pandemic.”

Marshall Henry: “The studio was finished just in time,” remembers Henry. “I went to Mali in January 2020. I brought the final equipment that he needed for the studio like cables, compressors and microphones and I recorded a little on the album. (bass) That turned out to have been perfect because it was really the last opportunity to bring suitcases of equipment into Mali!”

Vieux: “I said “Let’s go. Now we’re going to record the album!” We had time to record in the studio every day,” recalls Vieux. “We were making the album and we didn’t finish it but when we signed with World Circuit we said, “Now we have to give them the album!” So, we had to do the final production! We did it very quickly.”

Marshall Henry: “The album couldn’t have been arranged in this way if it wasn’t Covid time. Vieux was able to work on the arrangements for over a year, re-crafting the songs, adjusting guitar parts and thinking about which musicians to add,” Henry explained. “The one good thing about Covid was that Vieux had all this time at home to work on the album. That’s why it came out so beautifully.”

BE TOGETHER

Q: “Is it important to you to bring ideas about peace and social change in your music?”

Vieux: “It’s really important to me to have this peace in my music. In Mali, I don’t speak many times about the political stuff. I’m apolitic. Politics in Mali is no good. The political guys, they just see their own interest,” offers Vieux. “I never speak about politics but when I’m singing, for sure, I always say exactly what I want to say. In Mali, it’s becoming difficult between the people. It’s like separate parts and it’s very bad. I think what I have to do in my music, is to tell people to get together and have peace.”

Marshall Henry: “There’s a song on the new album “Be Together” about the people of Mali just being together, even if it’s different groups,” adds Henry. “There’s an incredible story about Vieux’s concert in Niger; It was going to be his second concert leaving Mali during Covid, all this time. So, the first concert he went to Morocco, the second concert was Niger. Because of the political problems in Mali, he couldn’t fly directly to Niger because the border was closed. The border to Burkina Faso was also closed, but Vieux knew how to get into Burkina Faso, to drive across. So, he drove his car from Bamako to Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso.”

Vieux: “A ten-hour drive.”

Marshall Henry: “And then he took a flight from Ouagadougou to Niamey, Niger. He played the concert. It was a beautiful concert,” Henry explains. “He flew back to get his car and as he was leaving Ouagadougou, there was a coup in Burkina Faso. He hears gunfire in the distance and he drives as fast as he can. He got out of Burkina and they closed the border completely, right after that. It’s an example of how hard it can be to be a musician in Mali.”

Vieux: “In Mali being a musician is like this. We don’t have choice and we have to do what we can do. It’s like this. I want my music to let people know about peace.”

This interview with Vieux Farka Touré was originally published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel on May 11, 2022 and was broadcast the same day on Transformation Highway with John Malkin on KZSC 88.1 FM / kzsc.org.